An A.I. Ponders Philosophical Questions Facing Self-Driving Cars

The debate over self-driving cars is perhaps the best microcosm we have to understand the issues facing Artificial Intelligence at large. The key question we’re asking of both technologies is a simple one – can we trust you? And yet, with minds like Stephen Hawking framing A.I. as “either the best thing, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity,” the answer could not be more important.

In the case of A.I., the great fear is that an Artificial Intelligence independent of human input would cease to value humanity. The corollary in the development of the self-driving car is that a machine that doesn’t require human input to get around will nonetheless have to make life-or-death decisions about humans. But those concerns haven’t slowed the race to develop A.I.s or self-driving cars in the slightest. For future-thinking companies with deep pockets like Google and Uber, the question is not, should we develop self-driving cars?, but rather, should future humans even be allowed to drive at all?

To explore the complex questions surrounding self-driving cars, researchers at Unanimous A.I. turned to UNU, our Swarm A.I. platform. After all, who better to weigh in on moral questions facing A.I. than an system designed to amplify human intelligence rather than replace it. So, what would happen if UNU was asked about fully-autonomous self-driving cars? Let’s start with a simple question…

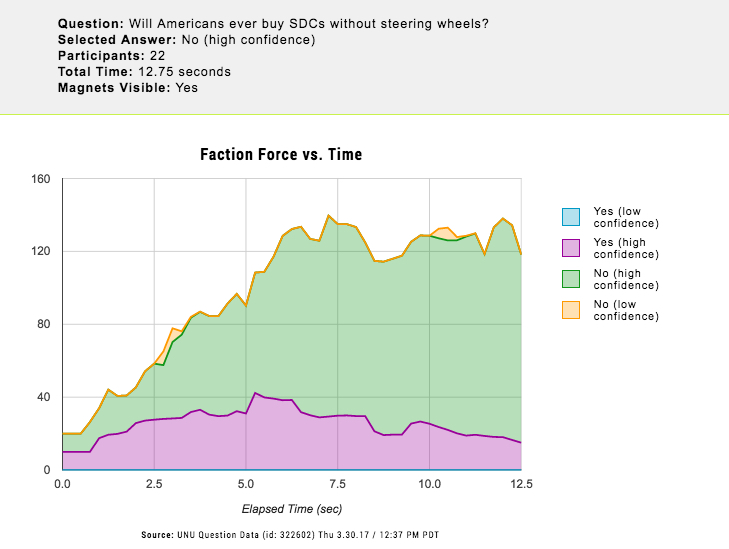

Shown above is a group of 22 Americans in the target demographic for self-driving cars thinking together as a swarm. We call this Swarm Insight, a real-time combination of human input and A.I. algorithms. Of course, if your business model depends on selling fully autonomous vehicles to the public, what you’re seeing is a nightmare. Out here in Silicon Valley, there are no fewer than 22 companies actively testing self-driving vehicles on our streets. The promise of an automotive future dominated by self-driving cars becomes more real every day. And yet, despite the inevitable march of progress, public acceptance of these vehicles at the moment still lags far behind manufacturers’ hopes and industry expectations.

Drilling down into the response using our Faction Analysis reveals the swarm’s overwhelming rejection of a future without some form of human control. UNU had difficulty even imagining a world in which Americans fully abdicated responsibility for driving to the car itself. Not coincidentally, the swarm was extremely confident – but not 100% certain – that a self-driving car would be responsible for the death of a pedestrian within the next three years.

While any death is certainly a tragedy, it’s important to put that number on context. At the moment, there is only one reported death due linked to self-driving cars, while more than 35,000 people were killed in traffic accidents in 2015. So, it’s clear that humans are by no means perfect drivers. But despite those numbers, a study published by Forbes claimed that only 10% of drivers would feel safer sharing the road with self-driving cars. These findings must be particularly disappointing to companies like Google and Uber, who have gone to great lengths to demonstrate the safety of their technology. Still, fairly or not, the worry over self-driving cars is hard to shake, especially when images of an overturned self-driving Uber recently went viral, causing the company to temporarily pause its testing.

THE SELF-DRIVING TROLLEY PROBLEM

It’s not hard to see why people hold self-driving cars to a higher standard than they do human drivers. Somehow, psychologically speaking, it seems easier to accept that humans will make mistakes. But, turning over complete control to an autonomous vehicle means that you’re giving that A.I. the authority to make thousands of decisions on your behalf, some of them with life-or-death consequences. In addition, the A.I. will have to consider not just the passengers in its own vehicle, but pedestrians and other motorists as well. So, now the question becomes more complicated – in an inevitable crash scenario, how should the A.I. choose between my life and yours?

To find out, we turned once more turned to UNU with an updated version of a well-known thought experiment called the Trolley Problem. The scenario presented by the Trolley Problem forces a person to choose between allowing a speeding trolley to run over five innocent people tied to the tracks, or pull a lever, diverting it so that only one man on an alternate track would be killed. This thought experiment might be an old one, but as Wired wrote recently and the Atlantic noted in 2015, “trolley problems have found new life in a more realistic application: research on driverless cars.”

Fully autonomous vehicles will soon be forced to make the kinds of moral decisions that have vexed philosophers for years. With that in mind, we asked UNU to consider a moral quandary in the vein of the Trolley Problem:

Suppose that a self-driving car spots a pedestrian in the road and must choose between killing the pedestrian or swerving into a tree, killing the occupant of the car. What should the self-driving car be programmed to do?

UNU had little difficulty in arriving at the conclusion that the self-driving car should be programmed to prioritize the life of the pedestrian over the occupant of the car, but its registered “Low Confidence” seems to suggest that the question was not an easy or comfortable one to answer. This response suggests the swarm’s conviction that potential customers for self-driving cars should be compelled to accept the risks associated with their chosen technology, up to and including mortal accountability. That might be one reason the supposed safety of self-driving cars could be a tough sell beyond the passionate early adopters. In fact, swarms revealed in 2016 that the most compelling reason to buy a self-driving car was not safety, but rather the liberation of “time to do other things.”

The most classic version of the Trolley Problem presents an even more difficult problem: Imagine the same scenario as above, but instead of a single pedestrian, the self-driving car must choose between the life of multiple pedestrians, or again steering the single occupant into the tree. Here, our Swarm A.I. technology showed a rather strong utilitarian streak, and again elected to swerve the car into the tree, albeit now with “High Confidence.”

Our early research thus suggests that self-driving cars should be programmed with utilitarian philosophies in mind, but these are but two scenarios of countless possibilities. More research is needed to know, for example, what UNU would suggest if the self-driving car had multiple occupants and would need to swerve to avoid a single pedestrian. But, whatever conclusions UNU arrives at have one fundamental advantage over the typical conception of A.I., its responses are derived from a group of people thinking together in a way that both mimics natural processes and amplifies their intelligence. That eliminates one of the core fears about Artificial Intelligence’s independence from humanity, and should give credence to the swarm’s suggestions about how to proceed.

So, what do we do? These are difficult questions and there are no easy solutions. And, as self-driving cars arc towards the mainstream, these philosophical thought experiments will quickly become practical questions. With that in mind, we asked UNU whether or not the government needed to be involved in the regulation of self-driving cars’ decision-making.

All politics aside, it is rare to see a group of disparate voters converge quickly on anything related to the government. Yet, when asked whether or not the government should be involved in the programming of decision-making processes, UNU registered its sentiment quickly and clearly: Yes and with “High Confidence.” In some sense, this response can be interpreted as a simple preference that someone else, in this case the government, be forced to wrestle with these tough questions. But that leaves us right where we started, wondering this time of the government, can we trust you?

Click the chart below to see replays of all UNU’s responses to this series of questions regarding self-driving cars. If you want us to do a deeper dive on this or any other topic, just drop us a line below. We’d love to hear from you.